Motown founder Berry Gordy plays the piano while a group of his record label employees, including Smokey Robinson (rear) and Stevie Wonder (right), clap and sing along. How could they ever have imagined what astonishments lay ahead for them? It was all so very unlikely. No, make that impossible.

On a cold October day in 1962, 45 Motown Records singers, musicians and chaperones stood shivering with excitement and nerves. They crowded together inside Studio A, the converted garage of a bungalow-style house that 32-year-old Motown founder Berry Gordy had bought, at 2648 West Grand Boulevard in Detroit. His neighbors were respectable strivers: Sykes Hernia Control Service and Phelps Funeral Parlor. Gordy, the great-grandson of a Georgia slave, had started his label in early 1959, the same year that Mattel’s plastic dream girl Barbie minced onto the scene.

Gordy’s troupe had mustered for the kickoff of the Motortown Revue, the company’s first extensive tour. A snapshot of the moment still hangs in the house on West Grand, which now serves as the Motown Museum. They stand clutching bulging purses and boxy cameras, tucked into tight chicken slacks and mohair sweaters, freshly barbered, manicured and beehived. The Supremes — Mary Wilson, Florence Ballard and Diane (later Diana) Ross — had just graduated from high school. The trio were thrilled to be going but worried that they hadn’t truly earned their seats on the bus. “Understand, we were favorites of Berry’s, little special girls,” recalls Wilson, now 74 and living in Los Angeles. “But unless you had a hit record, you were nobody at Motown. Nearly everyone else on the tour already had a hit.”

Those hit makers included Marvin Gaye, the Marvelettes, the Miracles, the Contours and Martha Reeves and the Vandellas. They were joined by newly signed 12-year-old phenom Stevland Hardaway Judkins — rechristened a more showbiz-sounding Little Stevie Wonder.

Mary Wells visits London before touring with the Beatles in 1964, marking the first time a Motown artist was to perform in the United Kingdom.

Also aboard, at 19, was Mary Wells, who had been crowned the Queen of Motown. She was regal with her Cleopatra eyeliner yet sweetly vulnerable on vinyl. Wells had been a working girl since age 12, when she had helped her single mother scrub frigid stairwells to support them both. “Until Motown, in Detroit, there were three big careers for a black girl,” Wells told me years later. “Babies, the factories or daywork. Period.” Gordy’s artists, all African American, were the sons and daughters of former sharecroppers, autoworkers, clerks, housekeepers and church deacons. At the time, Detroit had the fourth-largest black population in the nation, and it produced 50 percent of the world’s automobiles. The odds of escaping the factories or minimum wage work for any young person of color were dismal. But soon after Motown’s first hits blared from radios in the city’s schoolyards and housing projects, legions of young hopefuls besieged the hip, alluring enterprise on West Grand.

The Temptations (clockwise from left) Paul Williams, Eddie Kendricks, Otis Williams, David Ruffin and Melvin Franklin.

Those who made the cut were ambitious, pliant and eager to please. They’d do anything — sing background on demos at 3 a.m., hand clap, sweep floors, file session notes. Temptations lead singer David Ruffin helped Gordy’s father build the studio. In the Artists and Repertoire department, Martha Reeves was secretary and muse to 17 staff songwriters and producers. Gordy’s hit factory ran 24/7. Overall he paid poorly, but he plumped staff morale with bowling nights, picnics, poker and touch football games. A pot of chili bubbled in near perpetuity in the kitchen. The Hitsville troupe were a family of sorts — boisterous, competitive and tight.

Most of those dragging their luggage to the leased Motortown bus and five cars on that chilly day had never even left the state. In a phone interview from her home in Detroit, Martha Reeves, now 77, laughed at their utter naivete as they climbed aboard. “The bus was a broken-down Trailways with no toilet,” she remembers. “We had to lean on the window or on each other to try and sleep.” During the tour, which lasted from October through December, Reeves says the performers slept in hotels two nights per week, at most.

That grueling tour and the many that followed were part of Gordy’s audacious plan for integration — and domination — of the Top 100 pop chart. He announced his ambition on the building’s facade: Hitsville U.S.A. The lettering was painted in bold “Motown blue,” the same saturated hue on their now-iconic record labels.

The Marvelettes (from left): Wanda Young-Rogers, Georgeanna Tillman-Gordon, Katherine Anderson and Gladys Horton.

But how could his crew break through the stubborn segregation of a music industry that confined black 45s to “rhythm and blues” charts? In 1960, only four singles by African American artists reached the higher altitudes of the pop (that is, white) Top 100. “Crossover at that time meant that white people would buy your records,” recalls Smokey Robinson, who was present at the label’s inception. “Berry’s concept in starting Motown was to make music with a funky beat and great stories that would cross over.” Gordy’s hybrid product was a mélange of pop, R&B and even a touch of Vegas, shot with gospel harmonies and rhythms — in short, polyglot American. He began releasing records on three company labels: Tamla, Gordy and Motown.

Some striking demographics helped underwrite his gamble. Teenagers — those impulsive, hormonal buyers of 99-cent singles — were fast becoming the largest population group in the U.S., and they controlled billions of dollars a year in disposable cash. Would white kids spend their money on records by black artists? Gordy got his answer in 1961, when the Marvelettes’ “Please Mr. Postman” hit No. 1 on the pop chart. It appeared that kids didn’t care who was making the music if it was compelling and danceable enough. Given the almost limitless potential of the teen fan base, a tour introducing Motowners to live audiences on the East Coast and in the Deep South would be Berry Gordy’s moon shot.

And what a ride it has turned out to be. What colossal, long-playing reverb. It’s still hard to cruise a supermarket aisle or settle into brewpub trivia night without hearing the Motown sound pumping out of speakers.

Left to right: Mary Wilson, Diana Ross and Florence Ballard of the Supremes.

I’ve got sunshine on a cloudy day …

Ain’t no mountain high, ain’t no valley low …

Within a year of that first tour, Gordy’s company, begun with an $800 loan from his family’s credit fund, would post $4.5 million in revenue and launch a galaxy of singles into the Top 100 pop chart. Motown’s appeal quickly spanned the Atlantic, as the Supremes and the Beatles traded spots at No. 1. During its most successful years, from 1962 to 1971, Motown and its subsidiary labels racked up a stunning 180 No. 1 hits worldwide. Gordy liked to boast that 70 percent of his record sales were to white buyers.

Motown’s impact on popular culture is not so simply calculated. The Supremes did ads for those American staples, Coke and white bread; the cuddly Jackson 5 became a Saturday cartoon. Spotify still lists the Temptations’ “My Girl” as a top wedding song. Motown has lit up TV and movie screens, from the ominous chords of Marvin Gaye’s “I Heard It Through the Grapevine” opening The Big Chill to Broadway-musical and movie productions of Dreamgirls, the hit retooling of a Supremes-like saga. Over a third of Americans tuned in to the 1983 TV anniversary special Motown 25: Yesterday, Today and Forever. Yearly, 80,000 visitors pass through the museum on West Grand. And the museum is planning to expand. Ford Motor Co. and its union, UAW-Ford, have donated $6 million for a proposed $50 million expansion on adjacent land donated by Berry Gordy.

As for the label itself, Gordy sold it to MCA and Boston Ventures in 1988 for $61 million. He fretted that he had set his price too low, and that proved true. Polygram bought it for nearly five times that, $301 million, in 1993. Today the label is modest in size, part of the giant Universal Music Group. Reimagined as “The New Definition of Soul,” its artists include the protean Grammy-winning Erykah Badu and a rowdy posse of hip-hop acts: Lil Yachty, Lil Baby and social media star turned rapper Cuban Doll.

Clockwise from top left: William Guest, Merald “Bubba” Knight, Gladys Knight and Edward Patten.

How did Gordy achieve his audacious crossover dream? He declined to be interviewed for this story, but he has often credited his business model to his short tenure as an $86.40-a-week worker on a Lincoln-Mercury assembly line. He hated the work, but the plant’s precision and efficiency left a lasting impression. “Every day I’d watch how a bare metal frame rolling down the line would become a spanking brand-new car,” he has said. “What a great idea! Maybe I could do the same with my music. Create a place where a kid off the street could walk in one door an unknown, go through a process and come out a star.”

At Motown he built himself a Ford-tough quality control process that scrutinized every release. The music was heavy on studio-stamped style and far lighter in spirit than the unvarnished soul of Aretha Franklin (who recorded her biggest hits on Atlantic) and the Memphis vamps of Otis Redding and other Stax/Volt stars. Motown’s repetitive hooks burrowed into teen brains, and its thumping backbeat was something even the most rhythm-challenged kids could dance to. A stable of staff songwriters kept the hits coming.

Motown’s equipment and facilities were basic and often improvised. Studio A — also known as the Snakepit — had walls so flimsy that a sentinel was stationed outside the nearby bathroom, lest the roar of a flush ruin a take. Gordy confessed, “We would try anything to get a unique percussion sound: two blocks of wood slapped together … anything. I might see a producer dragging in bike chains or getting a whole group of people stomping on the floor.”

That make-it-do attitude extended to the performers. Gordy did sign a few polished, established groups, including Gladys Knight & the Pips, but mostly he mined and refined a lot of raw talent. Many of his singers were gospel-trained in Detroit’s African American churches. The masterful studio musicians, known as the Funk Brothers, were assembled by Artists and Repertoire director Mickey Stevenson, who combed the seediest bars and clubs in town for the best session men. Just as essential to the Motown sound were the Andantes, a sublime trio of backup singers.

Pictorial Press/Alamy

Clockwise from top left: William Guest, Merald “Bubba” Knight, Gladys Knight and Edward Patten.

Motown’s public face — its artists — got dance and voice training, as well as mandatory style and comportment lessons, in Motown’s fabled Artist Development department, run by Miss Maxine Powell. Wardrobe, grooming, diction — Miss Powell had it covered. Her coaching did help prepare the Supremes, who grew up in Detroit’s Brewster-Douglas projects, to meet England’s “queen mum” and navigate the formal etiquette of Japan.

On tour in America, the Motown artists faced a different sort of culture clash. One hot day in New Orleans, Mary Wells drew stares as she leaned into a drinking fountain and giddily assumed she had been recognized — until she looked up and saw the “Whites Only” sign. “In Detroit, we didn’t encounter a lot of segregation,” Mary Wilson says. “As we started touring we started understanding what our parents had been telling us about the South. We found out that there were places we couldn’t go.” She recalled the day when their bus pulled into the Heart of the South Motel in South Carolina. It had a pool! Hot, dusty and weary, the travelers dove in. “And all these other people started jumping out,” Wilson says. “All of them white.” Local deejays had been spinning Motown records all week, and at that tense moment, one of the songs was playing on a poolside radio. When the white hotel guests realized that the black swimmers were the ones they’d been listening to, “they came back in the pool,” Wilson says. “The rest of the day we partied.”

There were other incremental victories. Police stopped trying to enforce the rope lines that divided black and white audience members, and everyone danced together. But after their tour bus was shot at in Birmingham, Alabama, Martha Reeves understood the fear and fury caused by a busload of African American youths: “We were mistaken a lot for Freedom Riders trying to make a movement.” In July 1967, Reeves was onstage in Detroit, singing the smash “Dancing in the Street,” when she was called to the wings and asked to send the audience home to check on their families. The Motor City was burning. A police raid had triggered one of the bloodiest race riots in American history. It killed 43 and damaged over 2,000 buildings. Hitsville escaped the flames, but almost immediately, Reeves said, Motowners felt some misplaced blame. During a subsequent British tour, a reporter accused Reeves of being a militant leader. “They said that my song ‘Dancing in the Street’ was a call to riot. My Lord, it was a party song.”

More and more, old racial tensions and the churn of the growing civil rights movement were impossible to dance past. Motown artists who had sung their share of lovestruck pop tunes would turn their attention to real, biting commentary on social justice, with releases like Edwin Starr’s “War,” Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On” and Stevie Wonder’s “Living for the City.”

Berry Gordy founded Motown Records in 1959.

Meanwhile, as Detroit was trying to recover, Gordy moved his main operation to a larger, safer building downtown. His artists hated it. Worse, some were close to hitless without the magic of the Holland-Dozier-Holland songwriting team, who had departed the label in 1968 amid a flurry of lawsuits and countersuits over royalties. “From 1970 on, Berry wasn’t really interested in the record business,” observed his longtime marketing man and consigliere, Barney Ales.

In 1972, Gordy moved the company to Hollywood, setting up shop on Sunset Boulevard. He moved some of his blended family (he’s been married and divorced three times and has eight children) into a home in the Hollywood Hills. Down the street, there was a smaller rental home for Diana Ross. Their long affair — the stuff of Dreamgirls — was an open secret. Gordy was also candid about his desire to become a TV and movie mogul, with his protégé draped in furs and acclaim. Miss Ross would star in Lady Sings the Blues and the regrettable, Gordy-directed melodrama, Mahogany.

Back in Detroit, between 200 and 300 Motown employees had lost their jobs. Some, like the Contours’ Joe Billingslea, went back to the factory floors. Others, like the Four Tops, found new recording deals. But something precious had been lost. Duke Fakir, now 82 and the sole surviving original member of the Tops, says those still in Detroit were bereft. “Motown was more than brick and mortar. It was a huge part of our social life. We spent as much time there as we did at home.”

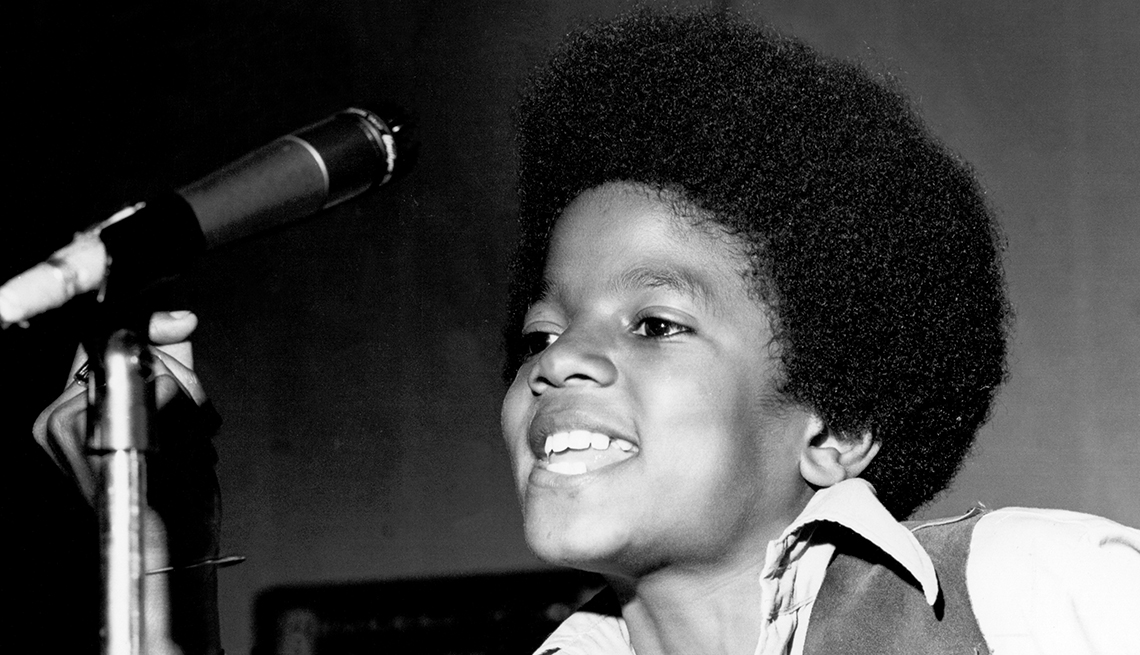

In Los Angeles, those adorable Jacksons helped carry the torch and the bottom line. In 1970, “I’ll Be There” sold over 3 million copies. As disco, funk and “adult contemporary” took hold, Motown signed that platform-booted superfreak Rick James as well as the Commodores, a former student band fronted by Lionel Richie. But there was a steady stream of artist defections — even Diana Ross left the label in 1981.

“I always knew I’d have to leave,” Michael Jackson told me in 1982, as he was about to release his monster hit, Thriller, his second solo album on the Epic label. He explained that even as a child, he knew that the Motown studio system was too confining for his singular vision. Nonetheless, MJ said he was grateful for the homeschooling in Studio A. He studied the producers with a silent obsession. “I was like a hawk preying in the night,” he said. “I’d watch everything.”

The Jackson 5 in 1971 (clockwise from bottom left): Michael, Tito, Jackie, Jermaine and Marlon.

Like many showbiz dynasties, Motown has also seen its share of tragic deaths. Temptation Paul Williams fatally shot himself two blocks from Hitsville. The Supremes’ Florence Ballard endured a heartrending spiral into depression and alcoholism and died of a heart attack at 32. Mary Wells lost her voice and her life to throat cancer at 49. A grieving Marvin Gaye could not perform live for four years after his duet partner, the stunning Tammi Terrell, collapsed in his arms onstage and died following brain surgery in 1970. Beset with drug problems, Gaye was shot to death by his father in 1984. Complications from substance abuse killed Temptation David Ruffin and Michael Jackson. They were all mourned like family by their labelmates.

Among the survivors of Motown’s first generation, the road still beckons for some. Martha Reeves performs with two of her sisters acting as latter-day Vandellas. Duke Fakir and his Tops tour 35 weeks a year. Otis Williams, the last original Temptation, is still on the road with “my guys.” There have been 22 replacements — so far. Yes, audiences still insist on the Tempts’ razor-sharp choreography — but sorry, folks, no more spins and splits. Williams is 77 and admits that some nights he’s bone-tired. “Yet here I stay. All we ever wanted to do was just sing and make the girls happy.”

It did start out simply — as did Mr. Ford’s basic Model T. In America, the product Gordy and his artists delivered was revolutionary in terms of black entrepreneurship and crossover clout. That loud, insistent backbeat was also heard worldwide. It prefigured today’s “global music” while delivering lifelong memories to millions. Gordy’s star-making machinery was primitive compared with today’s algorithm-driven merchandising. But in Motown’s frenzied boom years, Hitsville stamped out some remarkably durable goods. Solid state, still danceable and alluring, those blue-labeled 45s can claim the same honorific conferred on those other Detroit dream machines of yore: American classics.

In the beginning there was Berry Gordy, the founder of Motown records, a writer and producer of popular music that he hoped would one day reach all of young America, a man known for his impeccable ear and relentless drive. So it’s not surprising that the second act Gordy signed to his label was William “Smokey” Robinson, a teenage composer, and his singing group, the Miracles.

Like Gordy, Robinson was a prolific creator — he’s now credited with more than 4,000 songs and dozens of Top 40 hits, including “My Girl” for the Temptations, “My Guy” for Mary Wells and “Ain’t That Peculiar” for Marvin Gaye. But Robinson also went on to sing many of the timeless hits he created: “The Tracks of My Tears,” “I Second That Emotion” and “The Tears of a Clown,” for openers. He also became a Motown vice president, producer and talent scout. The image of Motown to this day is tied up with the image of Smokey Robinson — both are associated with class and taste and the ability to cross over to white audiences without ever losing the love and admiration of black fans.

Robinson has earned his place in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame and the Songwriters Hall of Fame and has been honored by the Kennedy Center. Two years ago he received the Library of Congress’ Gershwin Prize for Popular Song. These days his voice remains sweet and strong — he’s still recording and performing; in February and March he’ll be playing four shows at the Wynn resort in Las Vegas. At 78, he says he’s healthy and happy. When he’s not singing, he’s doing yoga, eating vegan or playing golf. In October we invited music journalist Touré to interview the Motown legend. Robinson was eager to talk about his role in the label’s history but was still mourning the August death of his friend, Queen of Soul Aretha Franklin — they’d known each other since she was 6 years old and he was 8 — so we’ll start there.

How are you feeling now about the loss of Aretha?

I’m still in recovery mode, because I love her and I’m going to miss our conversations and our getting together. But I know that spiritually she’s in a better place. She was suffering at the end there, and I don’t ever want to see her suffer. So now she’s cool, and I’m cool ’cause she’s cool.

You and Aretha grew up in Detroit, along with lots of stars — Jackie Wilson, Martha Reeves, Diana Ross, Mary Wells and more. The Detroit you grew up in was so musically fertile.

There were thousands upon thousands of talented people there. We used to have group battles on the street corners. There were groups that would outsing me and the Miracles.

Aretha Franklin and Smokey Robinson in 1982

But other cities are loaded with good musicians. What was different about Detroit and your era?

Berry Gordy. I believe there are talented people in every city, every town, every township, every village, every nook in the world. But Berry Gordy gave us an outlet.

What was unique about Berry?

He was a music man. When I met him, he was writing songs for Jackie Wilson and other people like that, and he was a record producer. Back in those days, especially if you were black, nobody was paying you what you should be paid, if they paid you at all. So Berry decided to start his own record company and gave us that outlet.

Some record execs succeed because they have the ears and some because they can make the business work.

Most record companies, back then, were run by lawyers or guys who just wanted to go into the record business for a hobby or something. But we had a music man at the helm. Somebody whose first love was music and producing records and writing songs. So that was a real asset for us.

Did he help you become a better songwriter?

Absolutely.

What did he teach you?

How to make my song be one idea. When I met Berry, the Miracles had gone to an audition with Jackie Wilson’s managers. Berry was there that day to hand in some new songs. We sang five songs I had written. Jackie Wilson’s managers didn’t like us at all, but after they had rejected us, Berry came out and said, “I liked a couple of your songs, man — where did you get them from?” I had 100 songs in a loose-leaf notebook. But most of them were haphazard, because my first verse had nothing to do with my second verse.

So he showed you how to make them more cohesive?

Absolutely.

What did he teach you?

How to make my song be one idea. When I met Berry, the Miracles had gone to an audition with Jackie Wilson’s managers. Berry was there that day to hand in some new songs. We sang five songs I had written. Jackie Wilson’s managers didn’t like us at all, but after they had rejected us, Berry came out and said, “I liked a couple of your songs, man — where did you get them from?” I had 100 songs in a loose-leaf notebook. But most of them were haphazard, because my first verse had nothing to do with my second verse.

So he showed you how to make them more cohesive?

Absolutely.

Joan Adlen/Getty Images

Smokey Robinson expresses his surprise midway through a performance when Berry Gordy joins him on stage in 1981.

Do you have a normal method of writing, like “I want to start with the rhythm and then get to the melody”?

No, there’s none of that, babe. Not for a real songwriter — there’s none of that. There’s no, “Let me start with this first every time,” because then you’re handicapping yourself.

When did you first think, I’m a good singer?

I never thought that. I’m not one of those people. I’m not an ego singer. I’ve never thought what you just said.

You’ve never thought that you were a good singer?

No. I think I feel songs. Whitney Houston was a great singer. Celine Dion is a great singer. Aretha Franklin was a great singer. I’m not in that category. I won’t fool myself. But I feel what I sing, and I think people can feel what I feel when I do.

When did you first think you could be a professional singer?

When I was a professional singer.

You didn’t realize you were good enough until then?

I grew up with some guys who could sing me under the table. All I know is that we were fortunate and blessed enough to meet a man who gave us a chance to make records.

OK, I want to talk about some of those records. “I Second That Emotion” is just an incredible performance. What’s the feeling that “I Second That Emotion” is working with?

When you’re musical, that stuff happens automatically. I do concerts every night, and it’s never the same. I’ve sung “Ooo Baby Baby” 500,000 times, but every night it’s brand-new because I don’t know how I’m going to deliver it. Whatever comes out of me that night is what it is.

What about “The Tears of a Clown”? I love that song.

Thank you. You can thank Stevie Wonder for that.

He wrote that?

I wrote the words; Stevie and Hank Cosby wrote the music. Stevie had recorded that track, and he couldn’t think of a song to go with it, so he gave it to me. I wanted to write something about the circus that would be touching to people. When I was a child, I heard a story about Pagliacci, the Italian clown. Everybody loved him and they cheered him, but when he went back to his dressing room he cried, because he didn’t have that kind of love from a woman. So that’s what “The Tears of a Clown” is about. It’s a version of Pagliacci’s life.

When you put it like that, the song could be a ballad.

The best version that I’ve ever heard of “The Tears of a Clown” is by a jazz singer who did it as a ballad. Her name is Nnenna Freelon. She had a violin crying in the background, and it was beautiful, because it’s a sad song. My version is upbeat only because of the musical track that Stevie gave me, but in essence it’s a sad song.

ou do make me want to cry with “The Tracks of My Tears.”

Well, thank you.

Tell me about that song.

“The Tracks of My Tears” originated with my guitarist, Marv Tarplin, and was cowritten with Pete Moore. Marv put his guitar riffs on tape and gave them to me to write lyrics. The first thing I came up with was, “Take a good look at my face, see my smiling side of the place, be the closest thing to trace, that you’re gone and I’m not.” And I said, “No, that’s not it.” Then, “It’s easy to trace that I miss you so much.” And I said, “No, that’s not it.” Then one day I was at my mirror, shaving, and I said, “What if a person cried until their tears had actually left tracks in their face?” Then I was able to finish the song.

So it took you a while to find that part to finish the song?

Yeah, yeah, but I did that in a couple months. “Cruisin’” took five years. Marv had given me the music, and I loved it. I used to go to sleep by it, I loved it so much. So I kept working on it. Then one day I was driving down Sunset Boulevard and I had my top down, and I said, “I’m just cruis-in’ down Sunset.” And then I said, “Cruisin’! That’s it!” I turned my car around, man. I want that gold!

Tell me about young Michael Jackson. What was it like having him around?

Young Michael Jackson was a man. He didn’t have a childhood. From the time he was, like, 8, they had him singing in the nightclubs. So when he got grown, he became a child because he could do it — he could play, he could do all those things he didn’t do as a child.

What about Marvin Gaye?

Marvin Gaye was my brother brother. We were together all the time, and he recorded my favorite album of all time, What’s Going On. He was one of the greatest singers ever. I used to tell him all the time, “You Marvinized my song, man.” Because he would do stuff vocally that I had never even dared to dream could be a part of the song.

What is it like to work with Stevie Wonder?

His music covers every genre you can think of — from gospel to jazz and everything in between. He’s just an extremely talented person, and he’s my brother. We always have a great time. We’d be working together and Stevie would come up to me and whisper in my ear, “Hey, Smoke, man, I’ma whoop your ass.” I mean, that’s how we are with each other.

Little Stevie Wonder in 1963

You were a central figure in the most important label of the century, in terms of music and in terms of social impact. What does that mean to you?

That means everything to me, man. That’s beyond our wildest dreams. Berry and I talk about it all the time. We never dared to dream that Motown would become what it has become. The very first day of Motown, there were five people there. Berry Gordy sat us down and said, “I’m going to start my own record company. We are not just going to make black music — we’re going to make music for the world.” That was our plan, and we did it.

1960

Motown releases its first hit single, “Money (That’s What I Want),” sung by Barrett Strong.

The Miracles featuring Smokey Robinson record “Shop Around,” the first Motown record to sell 1 million copies.

1961

The Marvelettes release “Please Mr. Postman.” This was the first Motown song to reach the No. 1 position on the Billboard Hot 100 pop singles chart.

1962

The Contours release “Do You Love Me?” — which was written for the Temptations. Because Gordy was unable to locate the group, the song was given to the Contours.

1963

Mary Wells appears on American Bandstand with Dick Clark.

1965

Six Motown releases reach No. 1, including “I Can’t Help Myself” by the Four Tops and “Stop! In the Name of Love” by the Supremes.

1966

1966

Gladys Knight & the Pips, rising stars from Atlanta, sign a record deal with Motown.

<

<